I don’t like quantum hackathons. They are 70% classical computer science, 20% quantum, and 10% something secret that every member of Planck Scale has taken a blood pact to never reveal. I’m quantum hardware and physics first, and quantum algorithms are one order removed from that. That makes for a fun hobby (everyone doing quantum hardware should naturally be well versed in the application of what they’re hoping to build). The classical aspect that dominates in quantum hackathons is two orders removed. I have a Diracian appreciation for the field, but it’s not what I do. Luckily, I went to high school with South Carolina’s best, who years after excel sheet meltdowns in Modern Physics and one memorable hour-late arrival to a C++ Database Design exam, have all gone into different fields and applications of computer science. Quantum hackathons are a game, and Planck Scale is a dream team with Michael Jordan, LeBron James, Kobe Bryant, Stephen Curry, and Michael Jordan again.

Martin Castellanos-Cubides, B. Chauhan, S. Chauhan, T. Seaman, and J. Telaak

Get Code To See the GitHub!

iQuHACK 2026 World Champions Announced: Biggest Quantum Hackathon Dominated by Planck Scale, and They’re The Best

by: Planck Scale

DCQO: Another Child of Simulated Annealing

The NVIDIA challenge started with a solution to the LABS problem that used a Digitized Counterdiabatic Quantum Optimization (DCQO) protocol to provide a “warm-start” set of solutions for a Memetic Tabu search (MTS). Although I can’t capture the full beauty of DCQO without going into the mathematical derivation, its main idea can be derived as follows:

Annealing involves taking the ground state of one quantum system under an initial Hamiltonian, adiabatically (slowly) changing the conditions of the system into those of a new Hamiltonian, and if you go slow enough you’ll remain in the ground state throughout the entire trip and end in the ground state of the new Hamiltonian. This principle by itself is beautiful, and annealers that use this principle are basically highly specialized quantum computers that compared to their generalized gate based counterparts actually produce usable results for a small subset of problems (as of February 15th 2026).

Through a foundational derivation that trotterizes evolution under non-commuting terms, we can do SIMULATED annealing on a gate based quantum computer. This Trotterization and thus the entire simulated annealing protocol works on the condition that time steps have to be very small, and that’s a problem for us because this requires an excessive amount of gate operations, all of which stack up errors. It’s highly impractical, and that’s why simulated annealing is mostly known for inspiring QAOA’s ansatz. However, from simulated annealing the DCQO protocol also arises!

If we consider evolution under the Schrödinger equation, we can home in on the transitions from the ground state to excited states during annealing. If we shift to the Heisenberg picture, we can define a Counterdiabatic (CD) term to equal the rate of change of the annealing Hamiltonian into excited states, and then define a new Hamiltonian that subtracts this CD term from the annealing Hamiltonian! Furthermore, if we have a quick transition between the initial and final Hamiltonian the CD term will dominate the evolution, and the original annealing term that was so impractical can be ignored. We essentially define an evolution that encodes the information of the annealing Hamiltonian, creates a shortcut between the initial and final points, and allows us to take this path while completely ignoring the original term we used to derive it!

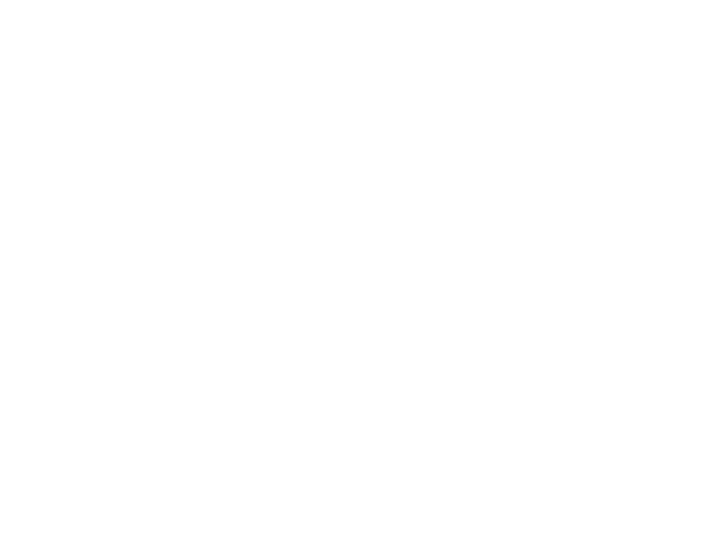

We end up with the benefits of simulated annealing (remaining in the ground state) without the drawback of having to simulate slow evolution through an excess of gates. Here is a good figure NVIDIA provided that captures this idea well, although I’ll point out a crucial flaw in this oversimplification in a bit!

Annealing and Counterdiabatic Driving

- Allows for quick, gate efficient annealing

My Edge

I like to do things a certain way. When I’m presented with a statement I break it down to its smallest components and write a proof. This is where I find my edge, as quantum hackathons are very “grab and go”, and people often don’t stop to analyse everything that they’re using to build their solution. Especially when it comes to working out a derivation for a quantum algorithm. For example, to derive DCQO you would need an intimate understanding of the Schrödinger equation, commutation, and the Heisenberg picture as well as how it outlines the framework for derivatives. Fortunately, I’ve spent hours becoming well versed in all of this. During my dive into the Heisenberg Picture specifically I cut off all my hair with scissors because it kept getting in my eyes while trying to read.

DCQO: First, We Will Assume the Penguin is a Sphere!

When it came time to analyse DCQO, I committed to doing a full derivation. And from my breakdown I noticed that the approximation under which we neglect annealing terms arises specifically from the function used to transition from the initial Hamiltonian to the final Hamiltonian. NVIDIA gave us functions we could prompt for parts of DCQO, one of which was this transition function, but because I had done the derivation of the protocol I didn’t have to treat the transition function as a black box.

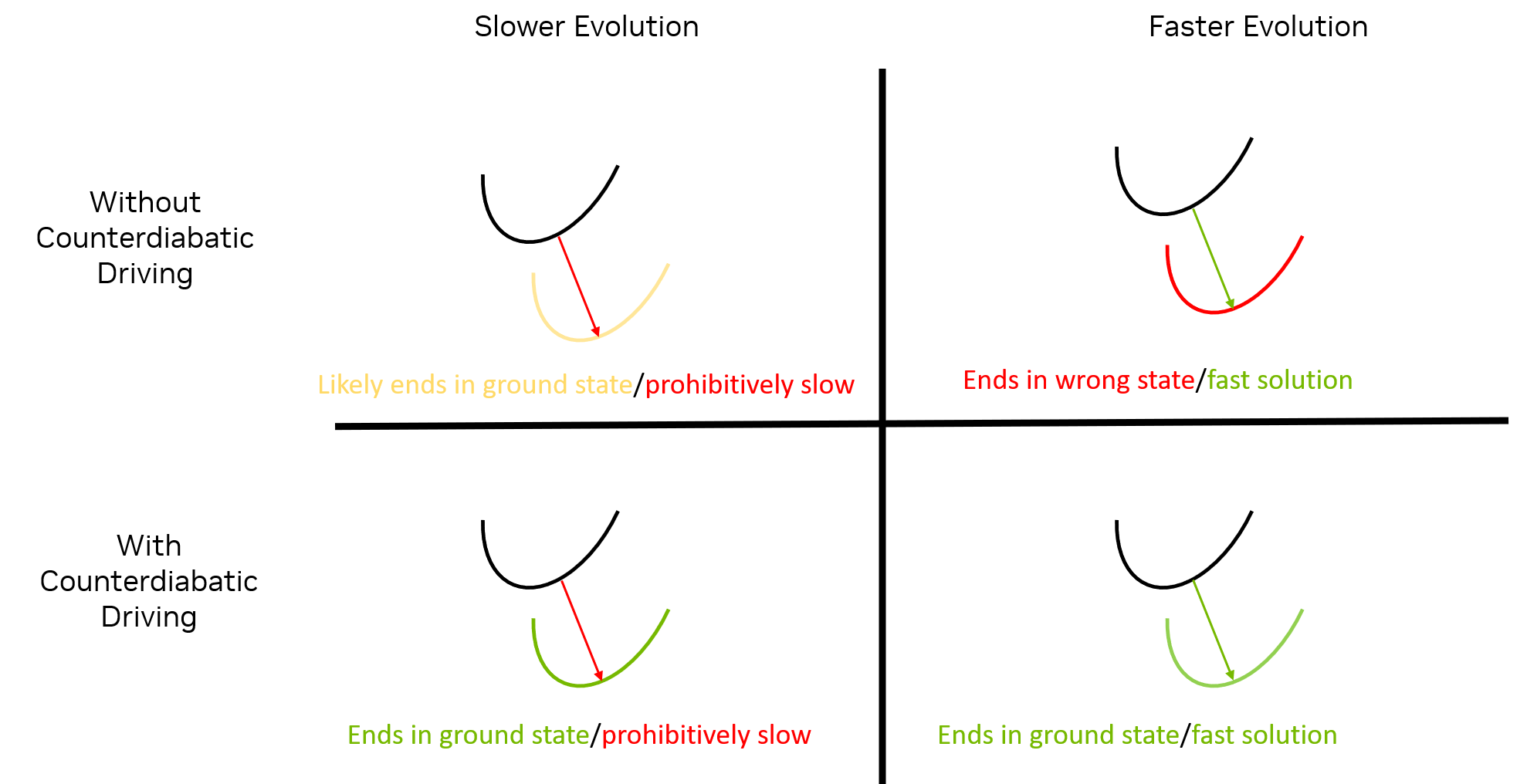

We received a sinusoidal transition function from nvidia, which I show here. The CD term dominates during quick transitions by the fact that it is multiplied by the derivative of the transition function. Quick transitions, large slopes, CD term dominates. But you’ll notice that any function with a slope gain greater than the slope of a straight line connecting the two points will eventually need to slow down. In the sinusoidal function for example, the area I’ve highlighted certainly does not have a large enough slope for the CD term to dominate, the approximation is no longer valid in this region! The annealing terms should become relevant again, and we should have to add them back for our system to remain in the ground state. The question then becomes how we should bring those terms back.

Transition Function for Simulated Annealing

- The rate at which the system is being transitioned from fully the initial Hamiltonian λ(t) = 0, to fully the final Hamiltonian λ(t) = 1.

The DCQO Hamiltonian and the Annealing Hamiltonian each break down into two qubit and four qubit interactions, the exact groups arise from the formulation of the LABS problem. We have freedom in determining the ordering of all these terms within a timestep. I came up with these three mixing protocols:

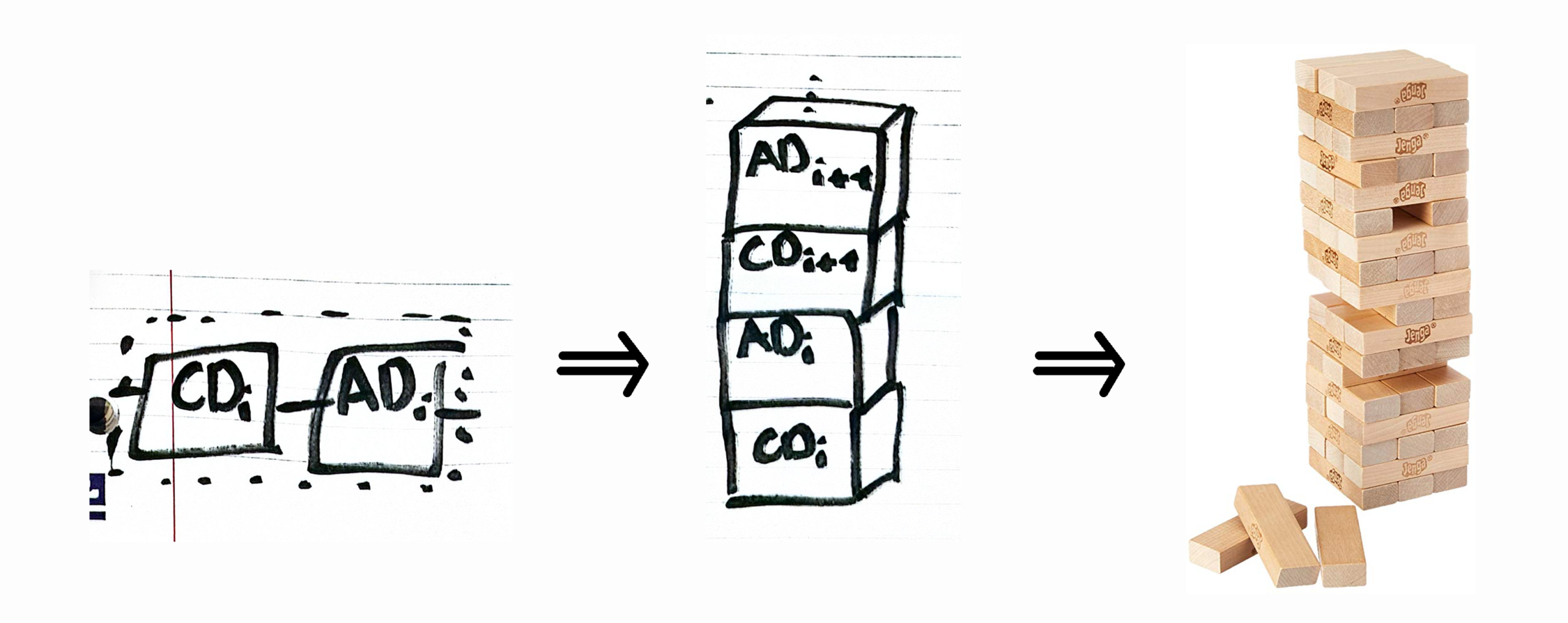

Jenga Mixing

The simplest of the three, which has complete separation of the CD and Annealing terms. In a single time step we first apply all CD gates, then all Annealing terms. If you turn it on its side it kind of looks like a Jenga tower.

Jenga Mixing

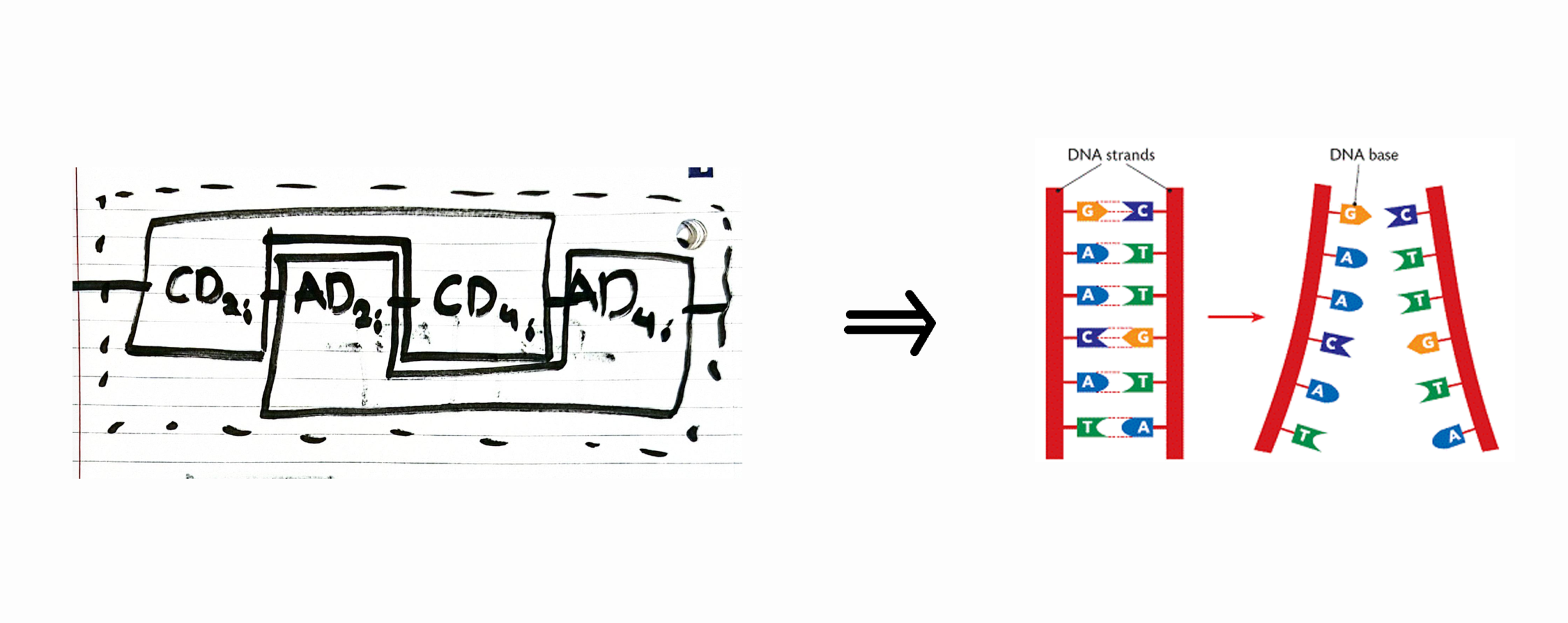

DNA Mixing

The next level of intertwinement separates the mixing between groups of 2 and groups of 4. In a single time step we first apply all 2 qubit CD gates, then all 2 qubit Annealing terms, then all 4 qubit CD gates, and finally all 4 qubit Annealing terms. The way these blocks form pairs is analogous to the nucleotide pairs of DNA.

DNA Mixing

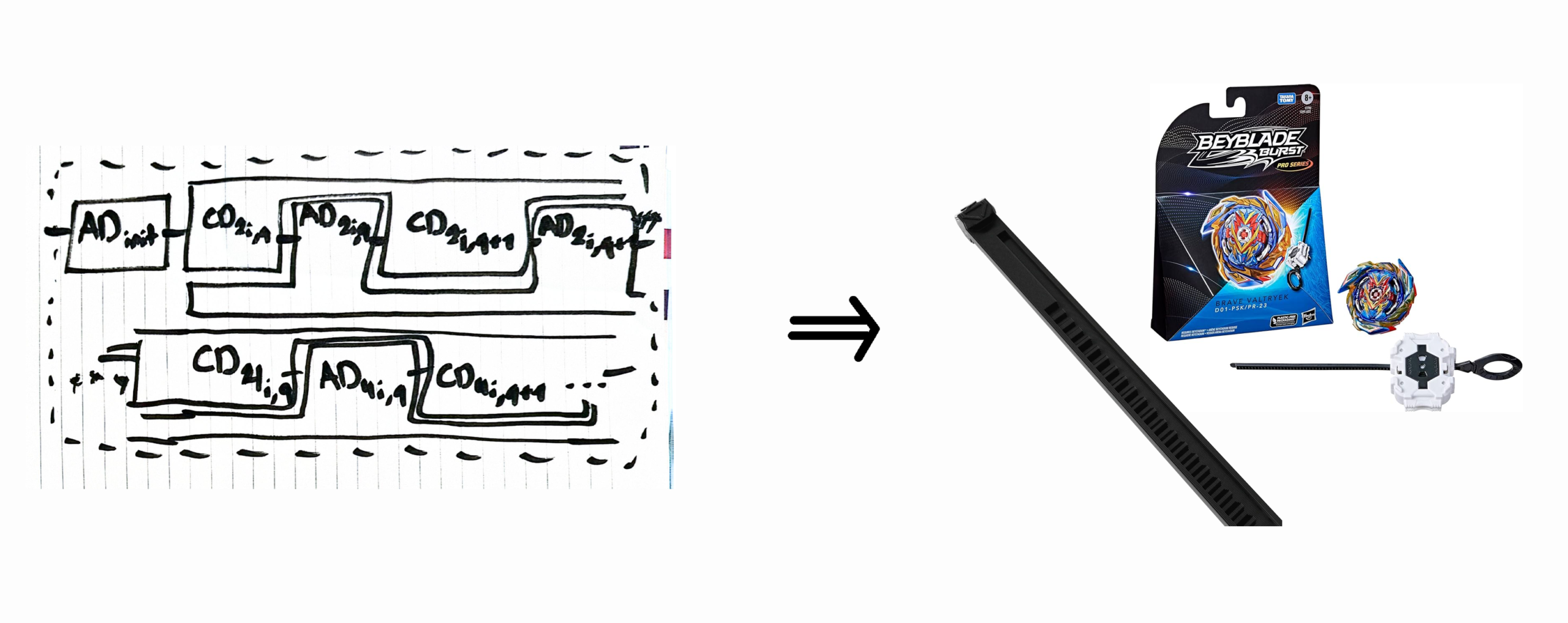

Beyblade Mixing

The final level of mixing is the most intertwined, where we apply the CD terms and Annealing terms in order for each individual grouping of qubits. The repeated alternation in each layer resembles the alternating teeth/ridges of a beyblade ripcord.

Beyblade Mixing

PCE: Now THIS is Encoding!

Pauli Coefficient Encoding (PCE) arose as a solution to a problem on the classical side of our project. In the DCQO method (and other methods we could have used like QAOA) the standard encoding had one qubit represent one variable, such that the 2n Hilbert Space could map to the 2n possible binary strings of length n. This would scale favorably for a real quantum system, but for a simulated quantum system (which is what we’re stuck with since real gate based devices are too noisy) this scaling is anything but. We were getting stuck around 30 qubits for this reason, and Benjamin suggested we look into alternative encoding schemes, linked me a paper he found on PCE and asked if it might be applicable to the LABS problem. It certainly was Benjamin, it certainly was.

My Edge

PCE is genius, I’m definitely going to keep it in my back pocket and I would encourage anyone interested in quantum algorithms to do the same. Where before we had 1:1 qubit:variable mapping, in PCE we make Pauli Strings and their observables our variables with a positive ⟨O⟩ corresponding to a 1 and a negative ⟨O⟩ corresponding to a -1. Although the exact values of the Pauli String observables is constrained (for example, we can’t have all Pauli strings ⟨O⟩ = 1) all combinations of SOME positive and negative values for each Pauli String is accessible to us, such that we can map one Pauli String to one variable of a binary string in the LABS problem. With 4 Pauli Observables ⟨X, Y, Z, I⟩ we have 4n-1 Pauli Strings for n qubits that we can map to variables of our binary string. We thus go from a 1:1 mapping scheme to a 1:4n-1 mapping scheme.

Looking at it though, I question the inclusion of the Identity gate. for example, if we had three qubits and wanted to use the Pauli String “IIZ” we would then have to enforce the hard constraint that the wavefunction MUST have a sign of ⟨IIZ⟩ that matches the optimal solution, and qubits 1 and 2 are irrelevant. Whereas if we did something like “ZZZ” the wavefunction could have a positive OR negative ⟨IIZ⟩ when we arrive at the optimal solution, and all qubits are relevant. Following this logic, our most expressible Pauli Strings are those that exclude the Identity gate all together. Although excluding it shrinks our space from 4n-1 to 3n the gain in expressibility justifies it. Understanding the theory behind this encoding scheme and the constraints of Pauli Observables for a given wavefunction allowed me to see this, call it a physicist’s instinct.

Do it For The Brev Credits

Presentation

My prediction was that we would see a lot of teams attempt a QAOA solution, considering its a standard algorithm that is relatively easy to implement. This prediction was right, and it was certainly a good call to stay away from it. Not only because it would have made us blend in with the crowd, but it just wasn’t a good method to implement. This came straight from the results of the paper linked to us at the start, and other groups’ attempt to use it anyways should serve as a cautionary tale of the mistakes that come with a blanket “grab and go” approach.

Besides that, there were only really two presentations of note. One other team attempted to use PCE, but they made two crucial mistakes. First, their answers were only converging up to about a string of length 20 which is a sign that either their PCE implementation was flawed, or the classical part of their hybrid algorithm didn’t have the steam to take full advantage of it. As I don’t have access to their code, I can’t comment on their PCE protocol, but I can say with certainty that they hadn’t achieved the level of classical optimization our team had achieved. I will elaborate on this dynamic later, but note that in quantum hackathons the bottleneck to good quantum is often classical. I don’t like it, it’s supposed to be a QUANTUM hackathon afterall, but if you wanna play the game you have to play by its rules. Or bring in 4 experts to beat that rule to death. The second mistake they made was that they failed to shrink their space to achieve maximal expressivity as I outlined in the previous section. This was common in most presentations, with everyone opting for the standard implementation of whatever algorithm they chose. Don’t get me wrong, sometimes things are standard for a reason, but if you take the time to understand WHY things are standard you’ll find that these algorithms are quite malleable.

There was one group I want to commend, the Harvard Blockheads. Their solution wasn’t flashy and they didn’t have any particularly good results, but it was quite impressive. They applied a protocol to condense four qubits into three. This doesn’t seem like much, and it’s almost certainly why they didn’t place, but from a technical standpoint condensing a four body problem into three bodies is very impressive. If I were to reform quantum hackathons to what I believe they SHOULD be, I would value stuff like that over blindly applying established protocols to a problem. However, I can’t deny the importance of proof of concept and must thus concede that this standard must remain. Which is why my advice for teams that can work with quantum algorithms and encoding protocols on a low level is to get people on the team who can dedicate themselves completely to the classical / proof of concept part of these challenges. Like we did.

Reflection: Why Are We The Dream Team?

The obvious answer is that we cover each other’s gaps, running like a well oiled machine that allows people to specialize in one thing. Occom’s razor. This is my fourth quantum hackathon, my first I flew solo on three days of methamphetamines, the second I paired up with friends of a friend that I didn’t really know, and the third I finally got Planck Scale (kinda) together. And even then we still had to calibrate a few things before we dominated this last event at MIT. We had to understand how each one of us works.

For example, Benjamin is the workhorse that will implement 70% of the classical solution. Sanjeev is the stop and smell the flowers type who gets easily distracted with small details of a solution, so we give him the staple second solution that’s more out there for him to fiddle with. In this case, what PCE was to our project. Joseph focuses mainly on data analysis and all the secret ingredients that win these events (which again, none of us will ever reveal. Regardless of how much you torture Joseph).

At our first quantum hackathon this dynamic wasn’t quite clear, and although I think we achieved a level of technical rigor in our solution that was unmatched at that event, we found we needed to work on what we present, how we present it, and how we make sure it gets on those final slides. Possibly the biggest change was adding Trent, who shares the workhorse role with Benjamin but also has a great chemistry with him. This allows them to bounce ideas back and forth about what to implement and how with an emphasis on getting the strongest possible base built. Whereas sanjeev will be talking about what material to use for the frame of this metaphorical skyscraper from the very start, and Joseph will add the secret design at the end that attracts all the rich people to rent a room they will leave empty for half the year (it’s a revolving door, it’s always a revolving door).

This article focuses on the quantum aspect of this project (because I’m the one writing it, and I don’t know if you’ve been able to tell but I’m kind of a quantum guy) but all of the classical work here went just as deep into computer science as the quantum work did in its respective field. It’s almost an insult that we only dedicated a single slide to it in our presentation. I think Nandini Gantayat on Trent’s LinkedIn said it best: “Being a python user I’m interested to understand how C++ was helpful in writing cuda kernels.” You and me both Nandini, you and me both.

I’ve said it a million times, but quantum hackathons are a game. You have to know how to play, and knowledge of that elusive 10% that we’re keeping to ourselves is part of the game. If it was anything that actually mattered I would share it for the sake of academic integrity, but it has absolutely nothing to do with anything quantum or classical and yet it’s the common thread between 95% of winning projects. If you knew what it was, you might also be inclined to say you don’t like quantum hackathons. But honestly? Quantum hackathons are like this girl I used to know in high school. 70% of her was focused on the wrong things, 10% left you rolling your eyes from the absurdity of it all, but that last 20% made you love the the whole damn thing. And that imperfection almost makes it better, makes it feel more real at the very least. It adds an uncertainty to the whole thing, and I guess it doesn’t really get more quantum than that. Except for her blonde friend quantum hardware/physics, which is 100% quantum. That’s the real love of my life, but that doesn’t mean I wouldn’t still hang out with quantum hackathons.

Plus, I’m sure quantum hackathons aren’t exactly ecstatic about 100% of me. So ultimately, who am I to judge?

Group Pictures

* still waiting on professional photos to be released, enjoy these in the meantime!